The Assembly in Paris

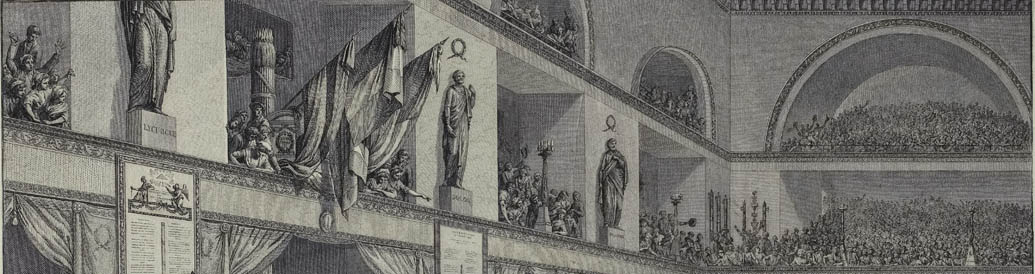

Starting in 1789, the Assembly’s meetings were opened to the public. Women and men who were interested, whether or not they had the right to vote, could come and listen to the debates from the stands located in the upper sections of the Salle du Manège. The people who frequented these meetings supported the left side of the Assembly more than the right, i.e. the more radical side. The deputies on the right side were thus often suspicious of these spectators. The distribution of entry tickets gradually made it possible to filter access to the auditorium. However, rather regularly, people could enter the Assembly to read petitions or march as a delegation during days of celebration.

Today, the terrace of the Feuillants is a place for strolling, but during the Revolution, the atmosphere was a different one altogether. Up until August 1792, the king and his royal court were at the Tuileries. The entire neighborhood was therefore filled with ministers. As for the National Assembly, it was off to the side, in the former indoor riding academy called the Salle de Manège. Some political clubs also moved into the area. Many journalists and deputies lived close by, in furnished apartments or hotel rooms. On the terrace, a person could run into elected officials, ministers and their employees, as well as journalists, wandering merchants or simply citizens who were interested in politics.

Location

ItineraryThe terrace of the Feuillants Café, Tuileries, in front of 230 rue de Rivoli

Suggestion

The Louvre and the Tuileries neighborhood

The Committee of Public Safety (Pavillon de Flore)

To find out more…

Laws to change the world

Built in 1720 for Louis XV’s horseback riding lessons, the Salle du Manège was imposing: it was 51 meters long, 14 meters wide and 9 meters high! From November 9, 1789 to May 9, 1793, the National Assembly held its sessions here after having been temporarily housed in the archbishopric, right next to Notre-Dame. Thus, it was here that French parliamentary life was invented and that the Republic took its first steps up until May 10, 1793, when the deputies moved into the large reception hall in the Tuileries, reconfigured for this purpose. Demolished in 1802 when the rue de Rivoli was extended, the Riding Academy was a testimony to a revolutionary utopia that succeeded: changing life through laws that were the same for all.

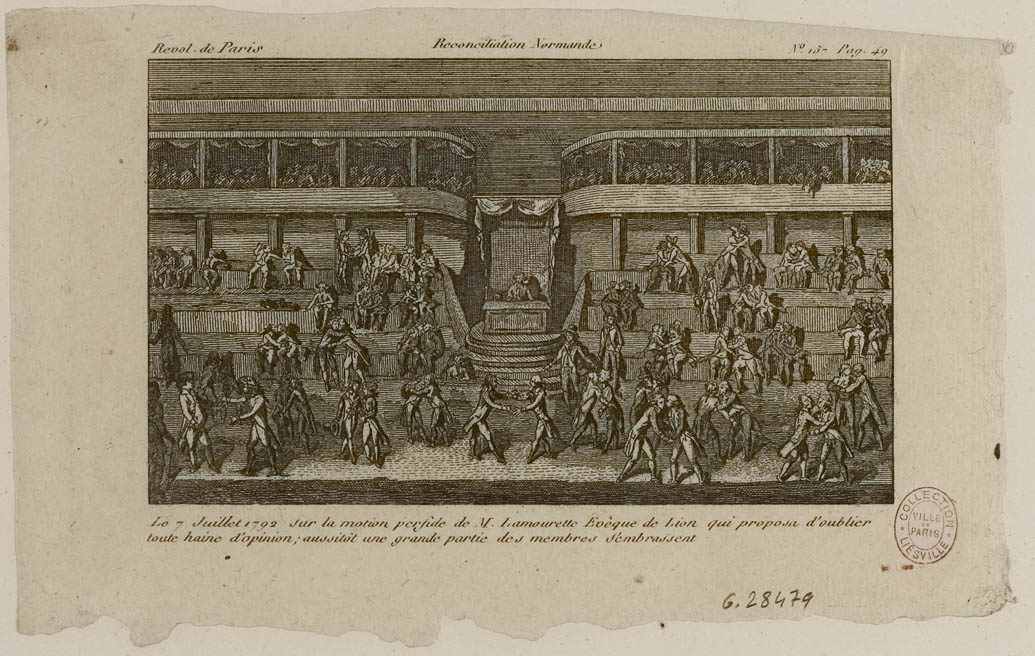

The Lamourette kiss

On July 7, 1792 a strange scene took place in the Riding Academy: upon the suggestion of deputy Lamourette, the bishop of Lyon, some Assembly members suddenly kissed one another in a sign of peace. Known as the “Lamourette kiss,” the event actually happened. Thanks to this idea, Lamourette tried to establish himself as the Assembly’s conciliator, since it was still profoundly divided regarding the king’s fate. Some were not fooled: immediately depicted in images, this kiss was only a communication strategy in order to let cooler heads prevail. In fact, the monarchy only had a few more weeks left…

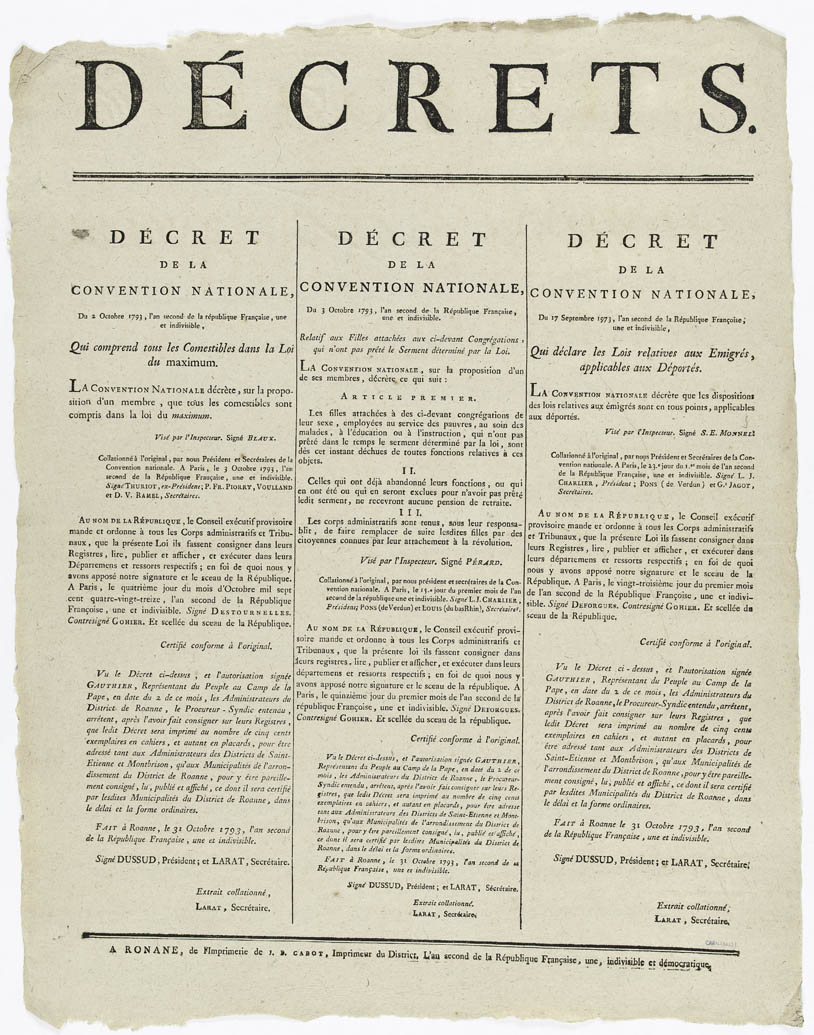

Laws of the General Maximum

As of 1792, the Commune of Paris capped the cost of essential products in Parisian markets. On May 4, 1793, deputies set the cost of bread for all of France. On September 29th of that same year, the law of the General Maximum was passed: under the pressure of the sans-culottes, there were now 39 essential products like meat, butter, oil, wine, wood for heating, fuel, steel, wool and tobacco. Salaries were also capped: those who passed these laws believed that any major inequality was a divisive factor that threatened the Republic’s survival.

February 4, 1794: the abolition of slavery

On February 4, 1794, the National Convention passed one of the first laws abolishing slavery in history. The French colonial empire possessed the largest sugar-producing island, a product highly consumed in Europe: in Saint-Domingue, in the West Indies, approximately 500,000 slaves, deported forcefully from Africa, worked in inhumane conditions. If French republicans immediately presented the event as proof of the superiority of their revolution over all others, the reality was quite different. On the one hand, some states in the US had already abolished slavery. On the other hand, French deputies faced a fait accompli: slavery was already abolished six months earlier on a portion of the island in order to end the slave revolts and enlist new soldiers in the war against England. Absent from the official discourse, slaves themselves were thus the main figures in their own emancipation.

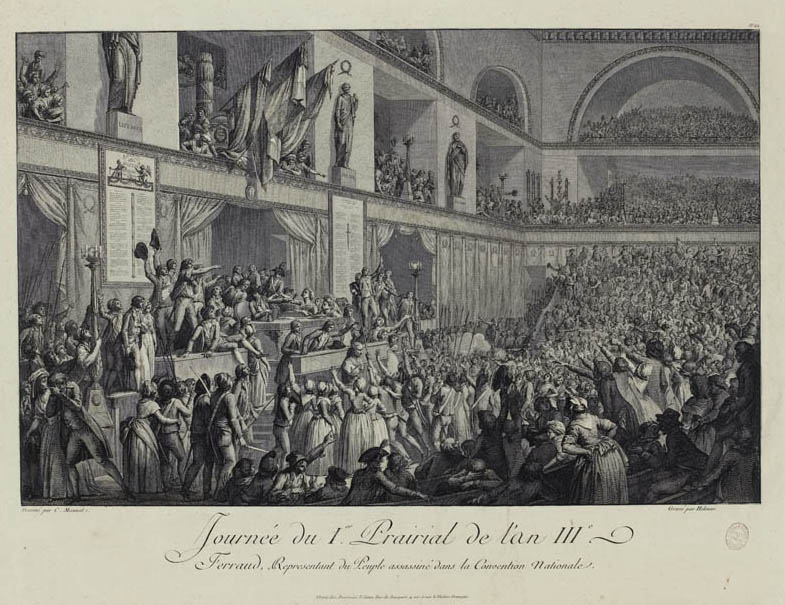

When the people held the deputies accountable

During the Revolution, the Assembly’s auditorium was invaded several times. On October 5, 1789, women from Parisian working-class neighborhoods occupied it for the first time. The strategy paid off: the king lowered the cost of bread, accepted the Declaration of the Rights of Men and left Versailles for Paris. On May 31st and then June 2, 1793, sans-culottes invaded the National Convention in their own turn so that the Girondin deputies would be banned. On September 5, 1793, the Montagnards, more radically minded, were targeted by insurgents who came to demand social measures. Lastly, on April 1st and May 20, 1795, insurgents demanding the application of the democratic and social constitution of 1793 and restrictions on the cost of bread, entered while brandishing the head of deputy Féraud. For some, these episodes were not only proof of the people’s savagery, but also the great weakness of the representative regime.

The madness of Théroigne de Méricourt

On May 13, 1793, a revolutionary woman from Liège, Théroigne de Méricourt, was violently attacked in front of the Riding Academy by other women. More radical, they reproached her for being a monarchist. The altercation quickly degenerated: Théroigne de Méricourt was stripped and spanked in public. The Paris deputy and journalist Marat intervened, but it was too late: she never recovered. Théroigne de Méricourt succumbed to madness and died in 1817 in the Salpêtrière hospital.