The Catacombs of Paris

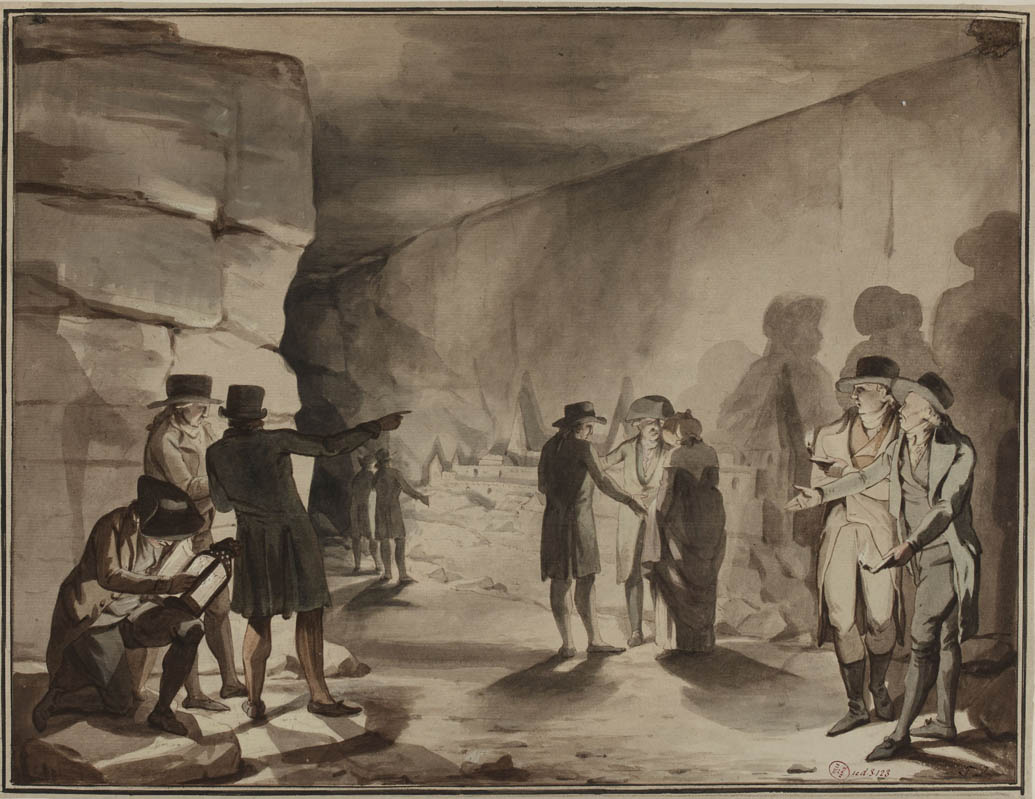

In 1789, the subsoil underneath this square already looked like Swiss cheese. Since the 13th century, limestone had been extracted from here in order to build houses in Paris. However, at the end of the 18th century, for hygienic reasons, it was decided to transfer the bones from the large Holy Innocents’ Cemetery – piled up in the open right next to Les Halles – to the former Tombe-Issoire quarries. On April 7, 1786, the underground site was blessed in order to welcome the remains of the dead who, from now on, would be far removed from the living. During the Revolution, the remains from other cemeteries within Paris were piled up here in their own right, and more often at night in order not to shock modern sensibilities. In the beginning, bones were quite simply dumped from the street level through airshafts. Then, workers from the quarries lined the tunnels with bones, giving the Catacombs its defining aspect.

Location

Itinerary3 avenue Rol-Tanguy

Suggestion

The Catacombs neighborhood

Hell’s Gate: Paris, an Open-Air Prison?

To find out more…

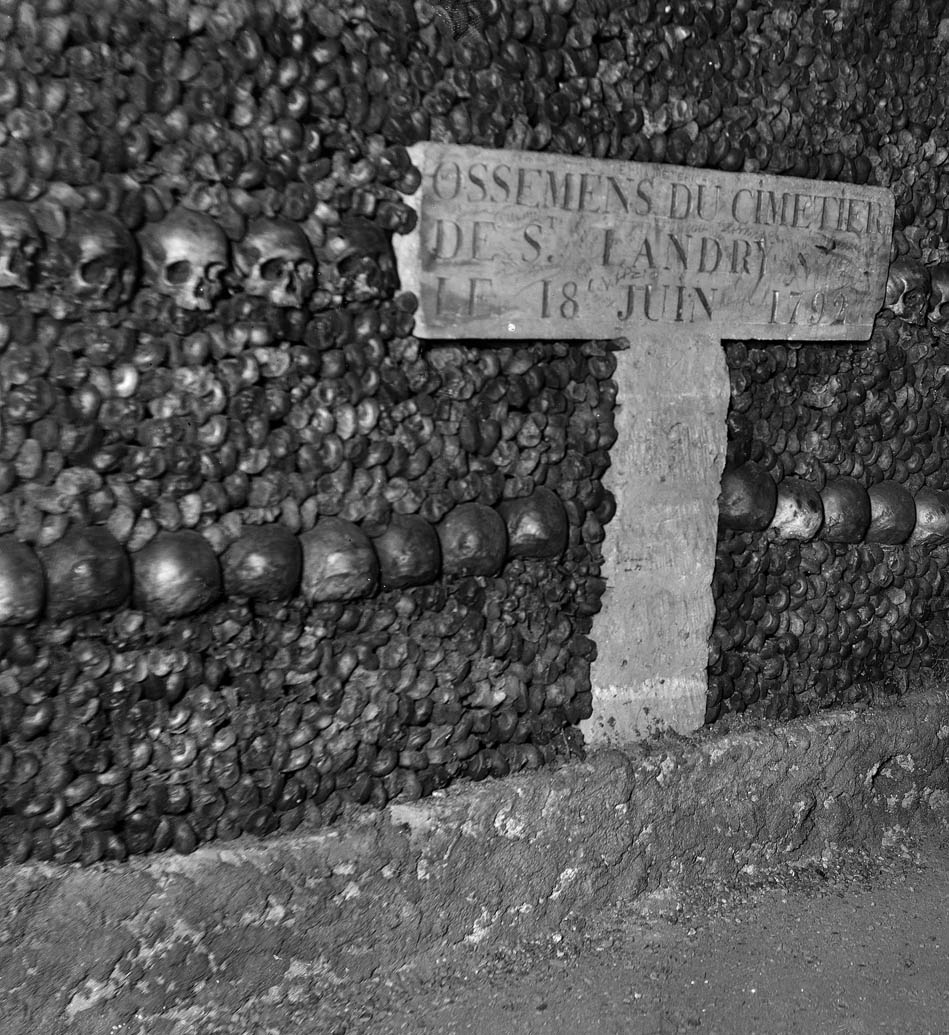

When Paris no longer wanted to see its dead

On June 18, 1972, the remains of the dead from the Saint-Landry church cemetery, located on Ile de la Cité, were exhumed. They were then taken to the Catacombs. The revolutionaries were simply continuing the policy of removing the dead from the city center, already started under the Ancien Régime. It’s not that the ossuary was a new concept, since ossuaries had existed in Paris for some time, but the fact that it was underground. The relationship with death was in the process of changing at the end of the 18th century. Parisians were distancing themselves from the traditions of the Catholic Church. They no longer felt the need to live near the deceased. Closed, then sold as national property, the Saint-Landry church was used as a dyeing factory. After the Revolution, it was not reopened for worship; instead it was destroyed under the Restoration in 1829.

Bury the dead of the Revolution

During and after the Revolution, bodies of the women and men who died during the events were transferred to the Catacombs. These included victims from every faction that existed at this time: those who died in the Saint-Antoine riots, killed in April 1789 for having rebelled against a decrease in wages, lay alongside the remains of prisoners massacred by revolutionaries in September 1792, as well as those who were guillotined. The fact that they were relegated to the obscurity of former quarries can be explained. Both the absolute monarchy as well as the Republic preferred hiding an upsetting reality: the Revolution was also a civil war.

A commemorative site of the Revolution?

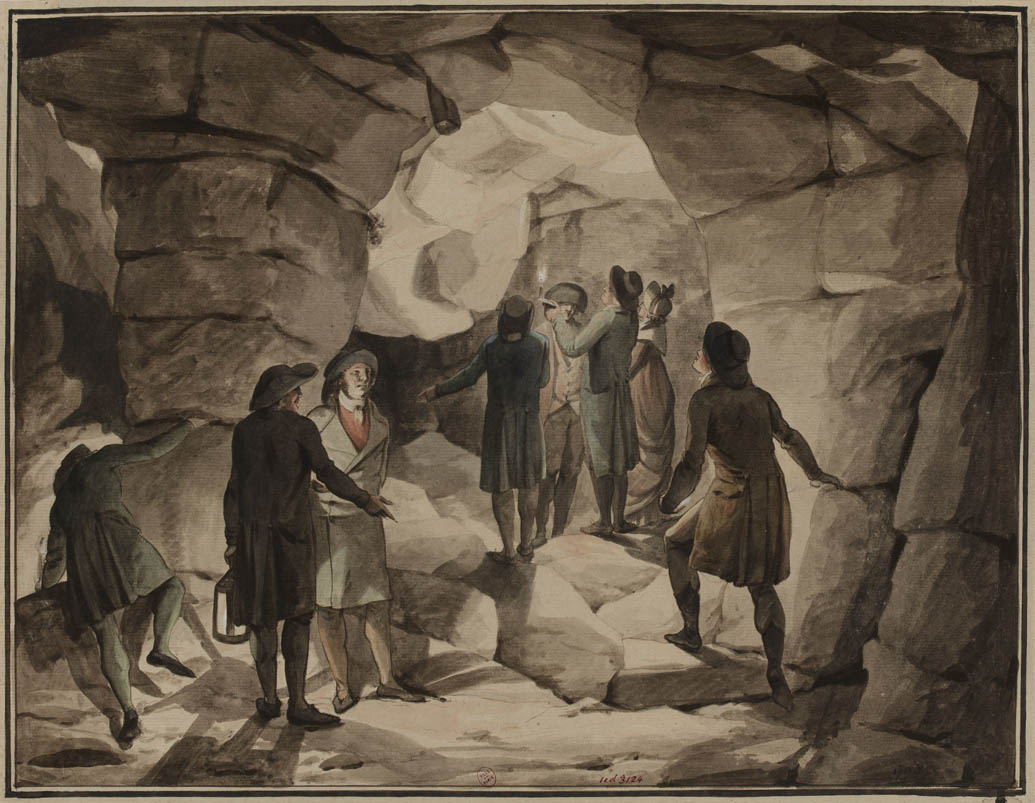

Starting in 1809, the Catacombs were opened to the public upon appointment. Major renovations had been carried out: quarry workers arranged the bones as if they were the walls that they usually built to fortify underground galleries. Louis-Etienne Héricart de Thury, the site’s new director, responded to requests from the families of the Revolution’s victims: “several families frequently asked permission to visit either the ashes of their ancestors collected from the different cemeteries in Paris, or the tomb of the victims from the massacres of September 2nd and 3rd [1792],” he confirmed. However, from the very beginning, and even before the Revolution, Héricart de Thury’s theatrical setting already attracted many visitors, often from abroad. In 1787, the Count of Artois, the brother of Louis XVI, visited; in 1814, it was the Austrian Emperor Francis I’s turn to visit.