"To the Great Men, a Grateful Homeland"

The Revolution needed examples to unite the French people. In the Middle Ages, these were knights and saints. During the Ancien Régime, illustrious men were glorified, often princes or nobles, far removed from the people. Now, it was time to honor great men: ordinary people who became great thanks to their courage or virtues. The Revolution needed to make this ascension possible: it was no longer birth or divine election, but abilities that created great actions. In England, the national heroes were celebrated in Westminster Cathedral. As for the French in the midst of revolution, they were inspired by Ancient Rome: they needed to have their own Panthéon.

Location

ItineraryPlace du Panthéon

Suggestion

The Panthéon and its neighborhood

The Revolution and Religious Faith

To find out more…

What to do with Saint Geneviève, the patron saint of Paris?

Before becoming the Panthéon, the church was dedicated to Saint Geneviève, the patron saint of Paris. The church’s transformation into a temple of the Revolution and then the Republic required removing all the décor that was dedicated to her… However, Mayor Bailly knew that many Parisians were still quite attached to this saint. In 1792, her relics were therefore transferred to the neighboring church of Saint-Etienne-du-Mont, where they continued to attract pilgrims. In the autumn of 1793, the shrine was destroyed and the relics were publicly burned on the Place de Grève. After the Revolution, in 1806, when the Panthéon was turned back into a church, the worship of Sainte Geneviève started anew. The Apotheosis of Saint Geneviève fresco, under the dome’s vault, demonstrates the reinstitution of the Catholic faith. During the 19th century, the building’s use changed three times. Frescos by Puvis de Chavannes, dedicated to the life of Sainte Geneviève were completed even though the Panthéon had once again become (in 1885) the necropolis for great men honored by the Republic.

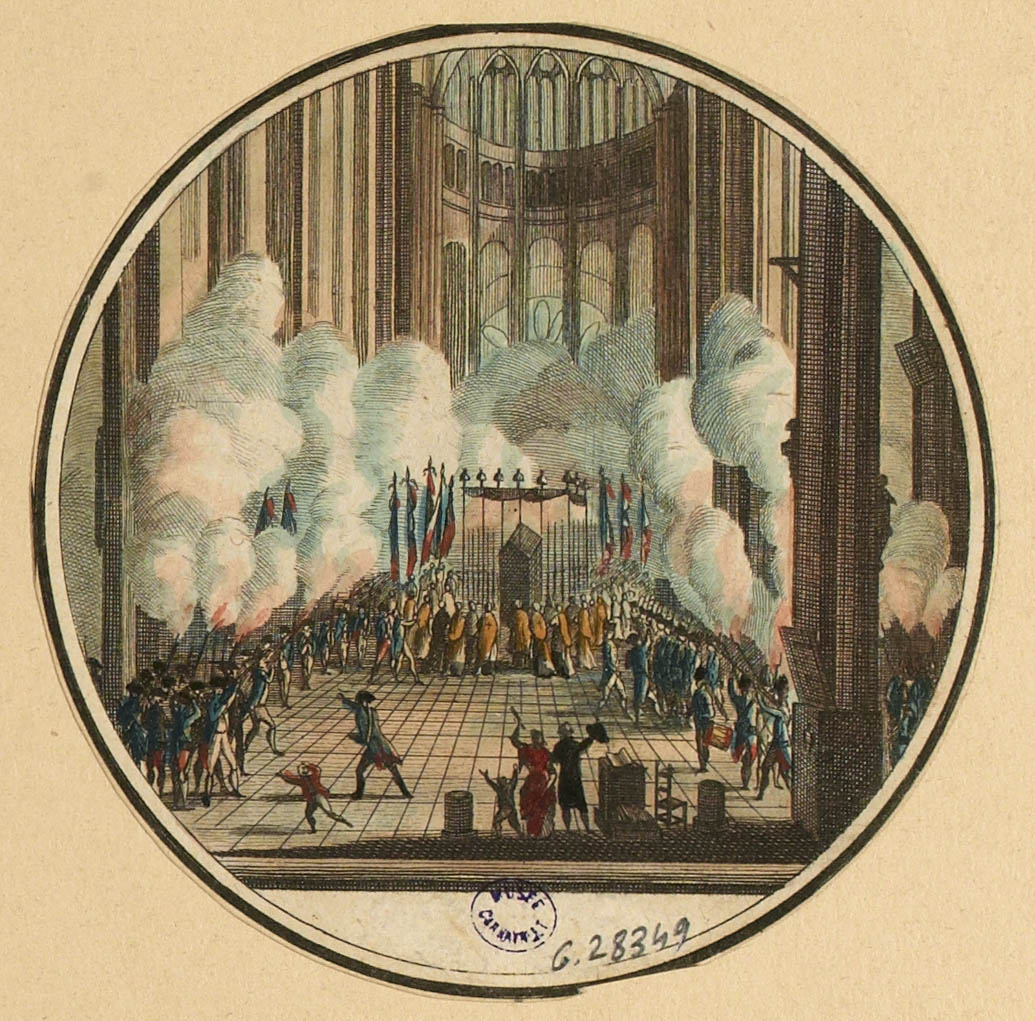

A sacred temple for the Republic

Not many of the monument’s vestiges remain from the 18th century. However, if you lift your eyes upon entering the nave, it is possible to glimpse a triangle with radiating beams of light. During the Revolution, this symbol was often chosen to represent the “Supreme being,” a sort of universal god: even if it was no longer a church, the Panthéon remained a sacred place, since it housed the remains of the Republic’s great men. Among the birds that surround the triangle, the rooster does not represent France, but a value that was very important during the Revolution: vigilance!

Mirabeau and Marat: two fallen heroes

Very popular since 1789, Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, Count of Mirabeau (1749-1791) was the first to enter the Panthéon in 1791… However, he was also the first to be expelled from it three years later: we know that, as of 1789, he conspired with Louis XVI in order to make sure the Revolution failed.

As for the Paris deputy and journalist Jean-Paul Marat, he lasted less than a year: assassinated in July 1793, he entered the Panthéon only to be removed several months later in February 1795, due to his extreme radicalism. His remains were not thrown into the sewers, contrary to what his enemies then claimed, but into a simple mass grave.

Vanished decor: the Declaration of the Rights of Men

These fragments of plaster are all that remain of the great allegory of the Declaration of the Rights of Men (1793). During the Revolution, this was located at the entrance of the Panthéon with other bas-reliefs. A large statue of the People in the guise of Hercules was supposed to welcome visitors. The message was clear: the great men of the Revolution fought for universal rights! All this décor was removed after 1815, during the Restoration.

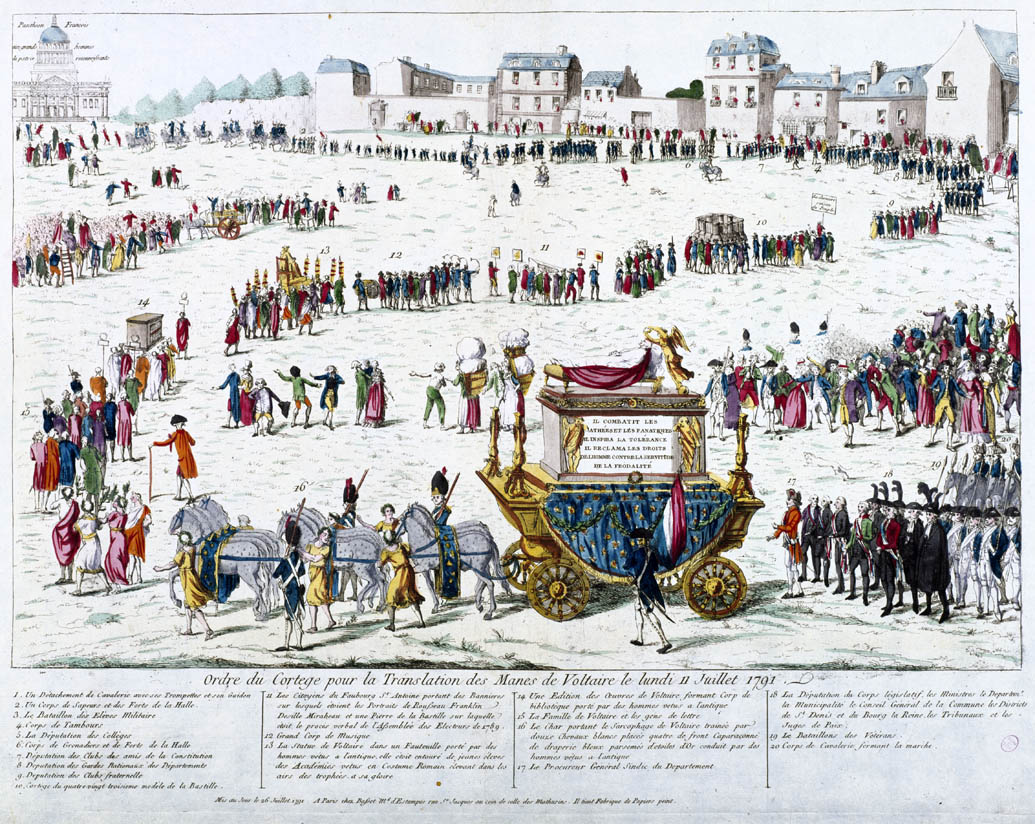

Voltaire and Rousseau, sworn enemies in death

Even if their ideas were more or less opposed, the two philosophers Voltaire and Rousseau were condemned to remain side by side for all eternity! Although they had been dead for some time, their remains were transferred to the Panthéon in 1791 for Voltaire, known for his fight against abuses and in support of tolerance, and in 1794 for Rousseau, famous for his appetite for equality. Accused of destroying the past, revolutionaries thus created their own origins: the Enlightenment. However, both Voltaire and Rousseau would have been surprised and unhappy to see themselves celebrated as the founding fathers of a revolution.

Honoring the values of the Republic

Under the entrance’s peristyle, two bas-reliefs date from the revolutionary period: Patriotic Devotion, which one can see on the door to the right, and Public Education, on the door to the left. Both were commissioned in order to replace the original religious decorations. The first, created by the sculptor Chaudet, represented a dying soldier supported by the spirit of Glory. The message is clear: great men are those who do not hesitate to take up arms for their country, even if means losing their life! The second bas-relief was sculpted in 1792/1793 by Lesueur: it is the Republic and not the Church that must take care of educating the French people, not for a privileged few, but for everyone.

A commemorative site of the Republic

Men from the Terror inside the Panthéon? The presence of this imposing group sculpted in honor of the National Convention is quite shocking. Even more so that it is placed in the choir of the former Sainte-Geneviève church. Called The National Convention (1792-1795), the first assembly of the First French Republic, habitually evokes repression and the guillotine… However, when it was commissioned from François-Léon Sicard at the beginning of the 20th century, Republicans from this time period wanted to remember that the National Convention was also at the origin of the democratic and social republic.

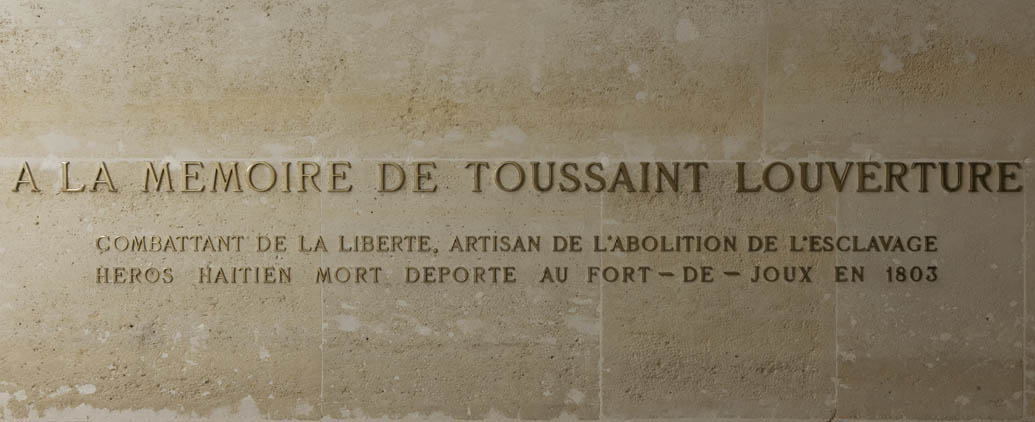

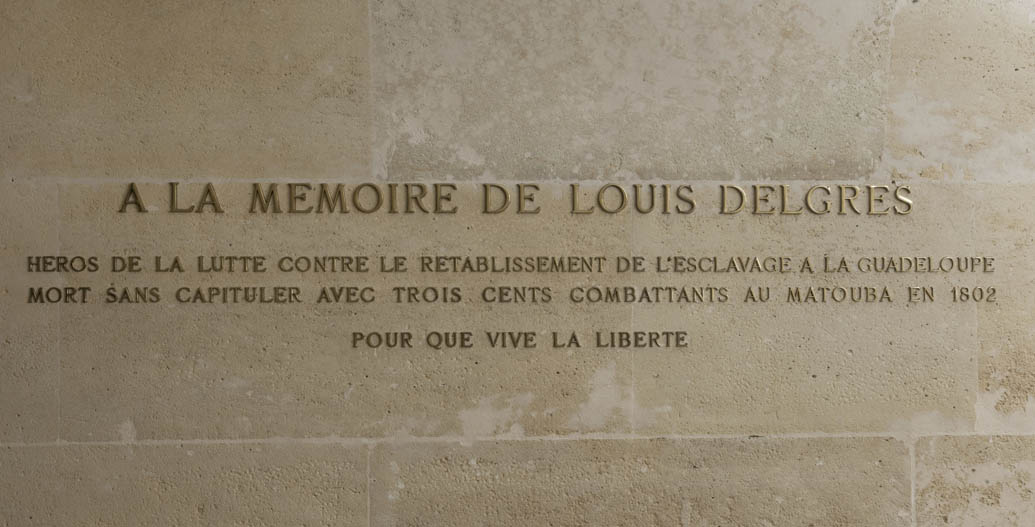

Were there Great Men from the colonies too?

Yes, but their respects were paid much later on. Not until 1989 did the French Republic pay tribute to revolutionaries from the colonies: Toussaint Louverture and Louis Delgrès. Both contributed to the abolition of the slave trade and slavery, passed on February 4, 1794. However, their backgrounds were quite different: a rich plantation owner, owner of slaves, abolitionist and a republican later on in life, Toussaint Louverture is considered to be one of the fathers of Saint-Domingue’s independence, in what is now called Haiti, in 1804. As for Louis Delgrès, he was an early abolitionist and republican. However, both died when Bonaparte wanted to reestablish slavery. The first died in 1803 in a prison in mainland France, while the second died in 1802 fighting against French troops.

Were there great revolutionary women?

Monge, Condorcet, Father Grégoire… In 1989, in honor of the French Revolution’s bicentennial, three “great men” were admitted to the Panthéon. As if there were no great revolutionary women! If some dreamed of seeing Olympe de Gouges, author of the Declaration of the Rights of Women and Female Citizens, they forgot that she died with her royalist convictions intact: difficult to defend in the temple of the Republic. On the other hand, other women could have aspired for this recognition: like Pauline Léon and Claire Lacombe, both revolutionary republicans who fought for the rights of women and social equality, or even Madame Roland, the most famous female political figure from her time period after Marie-Antoinette…