Picpus, a Commemorative Site of the Terror

Before the Revolution, monks occupied these premises. They were forced to leave in 1790: belonging to the State, the monastery became an asylum. From June 14-July 27, 1794, the remains of more than 1,300 people guillotined on the Place du Trône were buried in 300-meter long gardens. However, as of 1796, upon the instigation of a few noble women, several victims’ families joined forces in order to commemorate the memory of their loved ones: they bought back the land. The mass graves then became a commemorative site. All around it, a large cemetery was built. In 1805, nuns moved back onto the premises. In 1840, an expiatory chapel was built: the Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix chapel. Picpus is still one of the only private cemeteries in Paris today: only descendants of the families of the victims from the Terror can be buried here.

Location

Itinerary35 rue de Picpus

Suggestion

The Place de la Nation and its neighborhood

The Guillotine at Nation

To find out more…

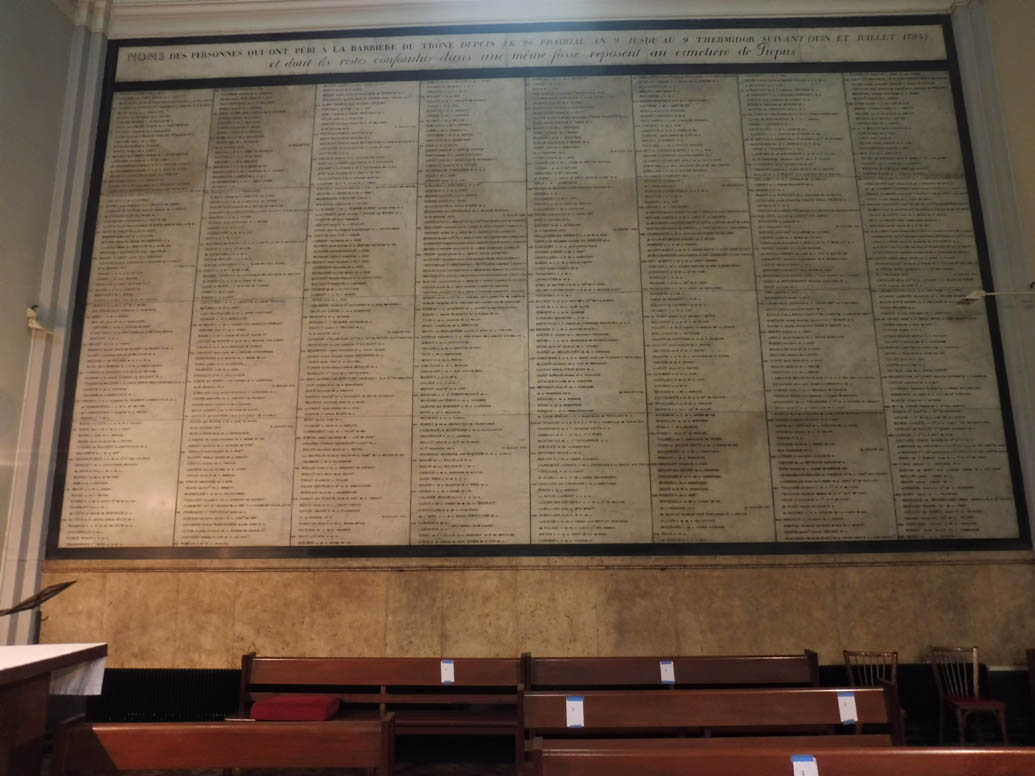

Remembering the names of the victims

Created at the end of the 18th century by the families of those guillotined, the lists of the victims of the Terror were used as commemorative objects. However, they were also used as weapons against the Revolution itself, in order to highlight its devastating effects: placed at the center of the expiatory chapel, these lists transform the political victims of the Revolution into Christian martyrs. Even if they help to identify the bodies in the mass grave, they need to be viewed prudently. Not only are they often inexact, but they mix everyone together: those who were condemned for their radical republicanism would turn over in their graves if they saw their names in this royalist commemorative site!

Picpus’s mass graves

Just like in the Errancis, Madeleine or the Sainte-Marguerite church cemeteries, which were used to bury those executed by the guillotine, the bodies here were discretely thrown into mass graves just after being decapitated on the Place du Trône-Renversé. For the revolutionaries, all the dead were equal: former nobles were therefore buried with the humblest of the people. The mass grave was also a way to forget the name of the people’s enemies: they were deprived of an individual tomb.

La Fayette’s Grave

What is General La Fayette, a hero of the American and French revolutions doing here? Dead in 1834, well after the Revolution, he was not decapitated during the Terror. The explanation can be found with his wife: Adrienne de Noailles was buried here in 1807 with her parents who were guillotined. In 1835, the body of the famous revolutionary was also placed here. However, his presence, in a cemetery dedicated to the victims of the Revolution, was then a subject of debate: during his funeral, only his family and close friends were authorized to enter the cemetery. Still today, every July 4th, the United States Ambassador comes to his tomb in memory of the services rendered in the American Revolution of 1776.

A commemorative site for the Counter-Revolution

Towards the back of the park, on the right, a cemetery is reserved for the families of the descendants of those who were guillotined on the Place de la Nation in the spring and summer of 1794. However, even if former nobles are the minority here, it was their descendants who, in the 19th century, wanted to turn this into a counter-revolutionary commemorative site. Today, in the cemetery and the chapel, one can find the most illustrious aristocratic names in France’s history: like Rochefoucault, Montmorency, Polignac, Rohan, Noailles, Lévis and Carency.