The Bastille

By the time the Revolution broke out, Parisians had already hated the Bastille for some time. Wider than it was tall, this fortress represented a defiant challenge to working-class neighborhoods. However, it was used less and less over the years: on July 14, 1789, insurgents freed only 7 prisoners… In other words, not a whole lot compared to the hundreds of prisoners rotting in other Parisian prisons, like Châtelet or the Abbaye. However, famous men were imprisoned here for their writings like Voltaire (in 1717 and 1726) and the Marquis de Sade (from 1784 to July 4, 1789). This is also where they imprisoned booksellers, printers or peddlers who did not respect government censorship. It should also be mentioned that this prison was very unusual: the king could imprison subjects here with a mere royal missive and did not need to rely on a judge to intervene. The Bastille represented both royal arbitrary power and the people’s glaring inability to freely express their thoughts. Consequently, its storming carried great symbolism.

Location

ItineraryPlace de la Bastille

Suggestion

The Bastille and its neighborhood

A Commemorative Site

To find out more…

A master escape artist: Latude

The Bastille was so despised that those who succeeded in escaping it became both martyrs and popular heroes. Their all-category champion was Jean-Henri Masers, aka the “Knight of Latude”: imprisoned for 35 years in the Bastille following a series of plots that failed, he succeeded in escaping from it several times. Only a few weeks after the storming of the Bastille, he became famous: the well-known painter Antoine Vestier exhibited this portrait of him at the famous Fine-Arts Salon, which was held at the Louvre. Depicting the fortress in the process of demolition, the painting was an unquestionable success.

Tourists come to see the Bastille

For a year and a half, the time that it took to demolish it, the Bastille was both a demolition site and an open-air museum. Parisians, as well as people from different departments throughout France, other European countries and even America, came to see the ruins of the fortress, which had become the symbol of the Revolution’s victory over despotism. Palloy, the contractor in charge of the demolition, even charged for guided visits. With this access to its hallways and former dungeons, visitors felt like they were able to finally pull back the curtains on the absolute monarchy.

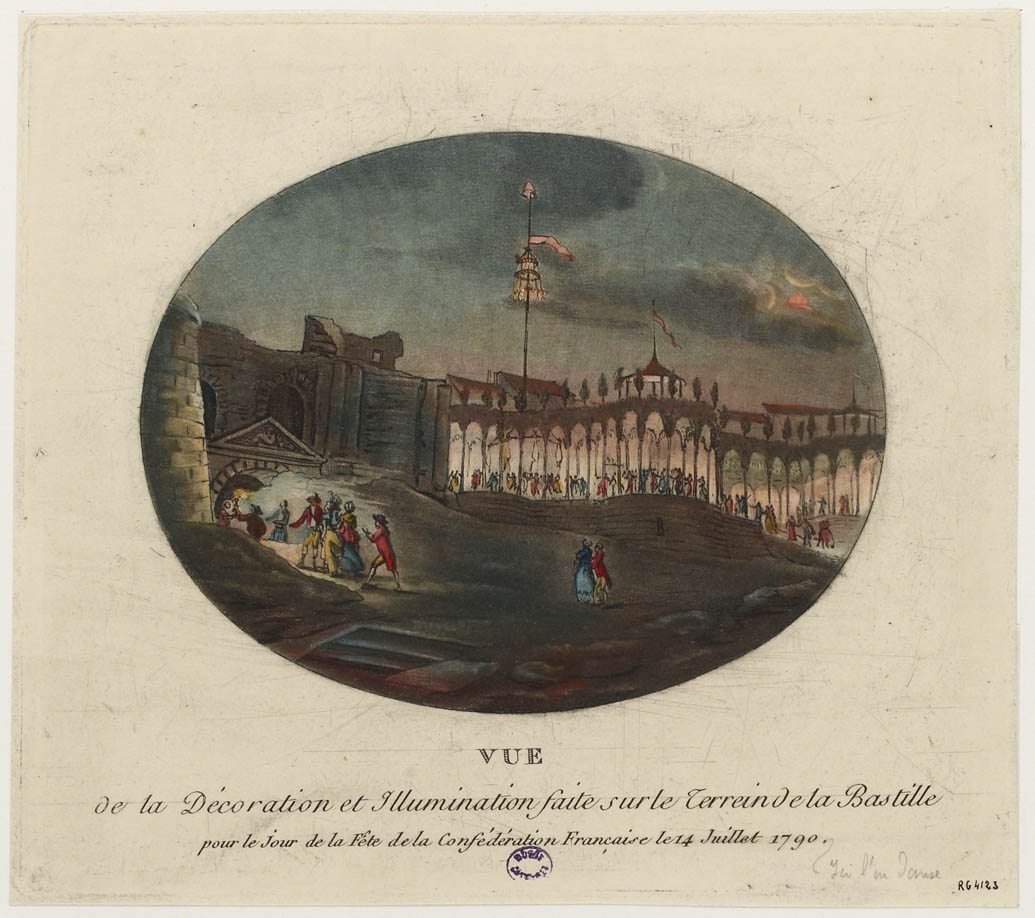

Dancing on the ruins of tyranny

“Let’s dance!” Planted in the middle of the celebration, the banner was explicit: the time for celebration had arrived. On July 18, 1790, one year after the storming of the Bastille, a dance was organized on the fortress’s ruins. Trees were planted for the occasion. Shields with the names of France’s 83 departments were placed around the walls that were still standing. An immense wooden structure decorated in tricolor ribbons was illuminated with candles. By dancing on the site where the king imprisoned his subjects, Parisians asserted the Revolution’s victory loud and clear, while others visited the bowels of the fortress at night.