The Carnavalet Museum

The Carnavalet-History of Paris Museum displays the world’s largest collection of paintings, prints, sculptures as well as medals, furniture and daily objects from the French Revolution. This collection comes in large part from a donation made in 1880 by Count Alfred de Liesville.

Location

ItineraryAt the corner of rue de Sévigné and rue des Francs-Bourgeois

Suggestion

The Carnavalet Museum and its neighborhood

The Theater of the Marais or “Theater Beaumarchais”

To find out more…

The deathbed of Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, a martyr of freedom

In 1989, during the French Revolution’s bicentennial, the collections of the Carnavalet-History of Paris Museum, before then simply displayed in the Hôtel Carnavalet, were also transferred to the adjacent building: the Hôtel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau. This is a commemorative site of the Revolution: it belonged to the deputy Louis-Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, assassinated on January 20, 1793 in the Palais-Royal for having voted for the death of the king. He then became one of the first three “martyrs of Freedom.” His body was displayed on the Place des Piques (currently Place Vendôme), in the home of his brother Félix: the Hôtel de Chimay. Afterwards, his bust and portrait decorated revolutionary celebrations and tribunals, along with Marat, a journalist and deputy of Paris.

The Revolution in paintings and drawings

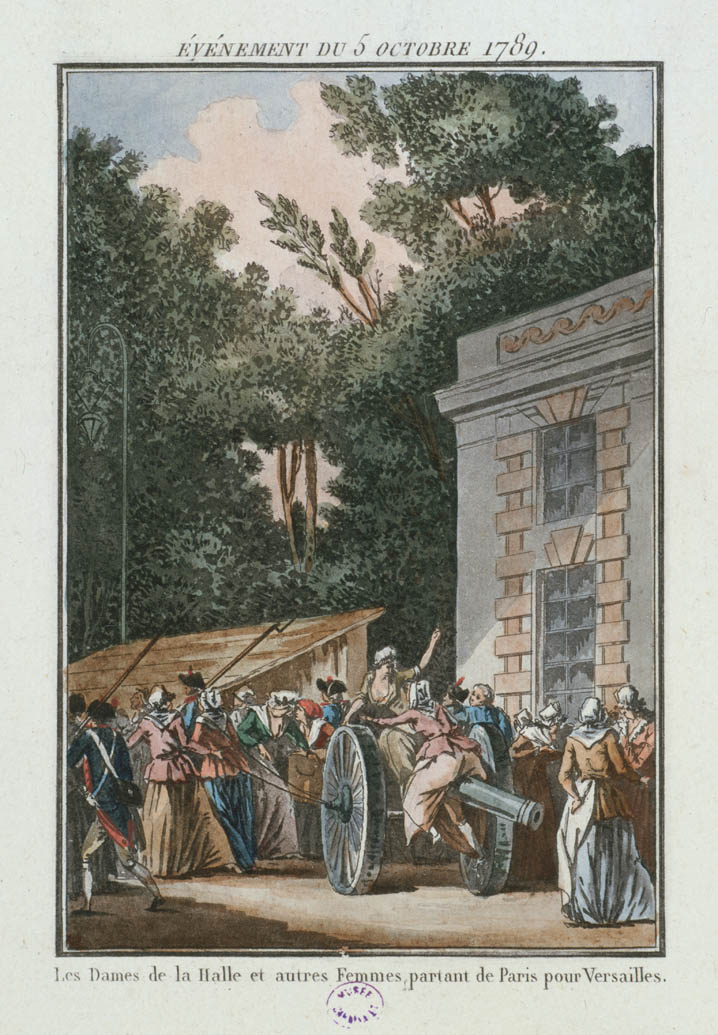

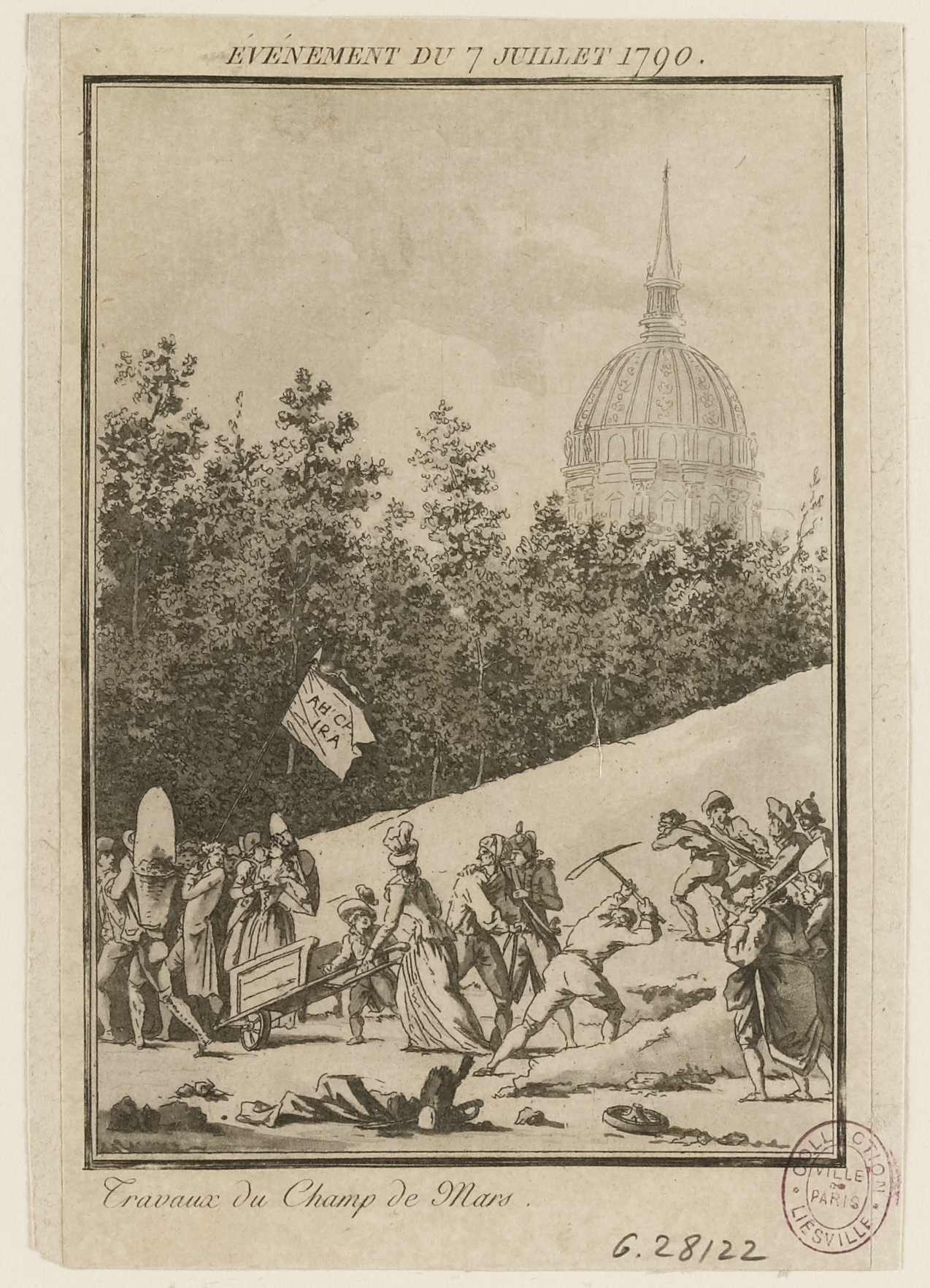

The Carnavalet-History of Paris Museum proposes a large collection of paintings, drawings and engravings. During the Revolution, major events were learned about either through hearsay, written documents or images. Some paintings were used to commemorate, or even embellish facts, in the manner of this Festival of the Federation, which Charles Thévenin depicted as a time of jubilation and unity even though he painted this work right when the king was attempting to flee the country, thereby renouncing the oath that he had just made to obey the law. On a day-to-day basis, it were drawings, less expensive, and engravings that informed Parisians of what was going on: the Janinet collection, kept at Carnavalet, retraces the major events of the Revolution with precision, like the image of women leaving from the Conférence tollgate for Versailles on October 5, 1789. The museum also has a famous collection of gouache paintings made by Jean-Baptiste Lesueur: they were probably used as small figurines for street theater, in which the events of the Revolution were replayed.

When Parisian interior decor was inspired by the Revolution

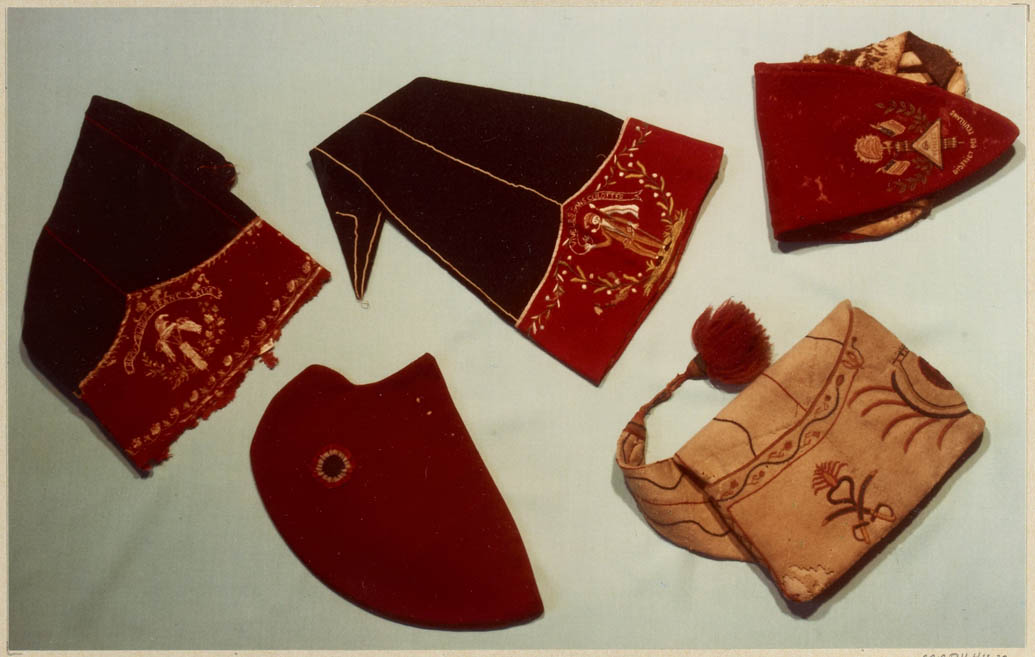

The Carnavalet-History of Paris Museum displays many objects decorated with revolutionary patterns and symbols: red bonnets, sans-culottes, tricolor cockades, patriotic mottos, etc. For Parisians, the Revolution was not an abstract thing: it was a new lifestyle! And when the Revolution turned into civil war, decorating one’s interior with a few revolutionary symbols also made it possible to avoid being suspected of counter-revolutionary activities…

Revolutionary clothing

At the end of the 18th century, revolutionary ideas even influenced clothing trends. “Common people” were known as “sans-culottes,” because they refused to wear the “knee-breeches” or “culottes” worn by the bourgeoisie and nobility. Patriotic lines of clothing multiplied: it was good to show that you supported the Revolution when you were out and about! On a day-to-day basis, it was the tricolor cockade, with the Revolution’s colors of blue, white and red, which allowed a person to display their support for the Revolution. And after 1793, it was the Phrygian cap, a symbol of freedom since Antiquity.

The monarchy’s memory

The Carnavalet-History of Paris Museum is one of the rare public establishments to display objects from monarchist and counter-revolutionary culture: furniture from the room in which the royal family was imprisoned in the Temple fortress, keepsakes, locks of hair preserved as relics. This material heritage considerably helped uphold the memory of the victims of the Revolution. Broadly circulated at this time, the many images representing Louis XVI saying his goodbyes to the queen and his children are interesting: they present the political condemnation of the former sovereigns as the persecution of an innocent family.