The Festival of the Federation

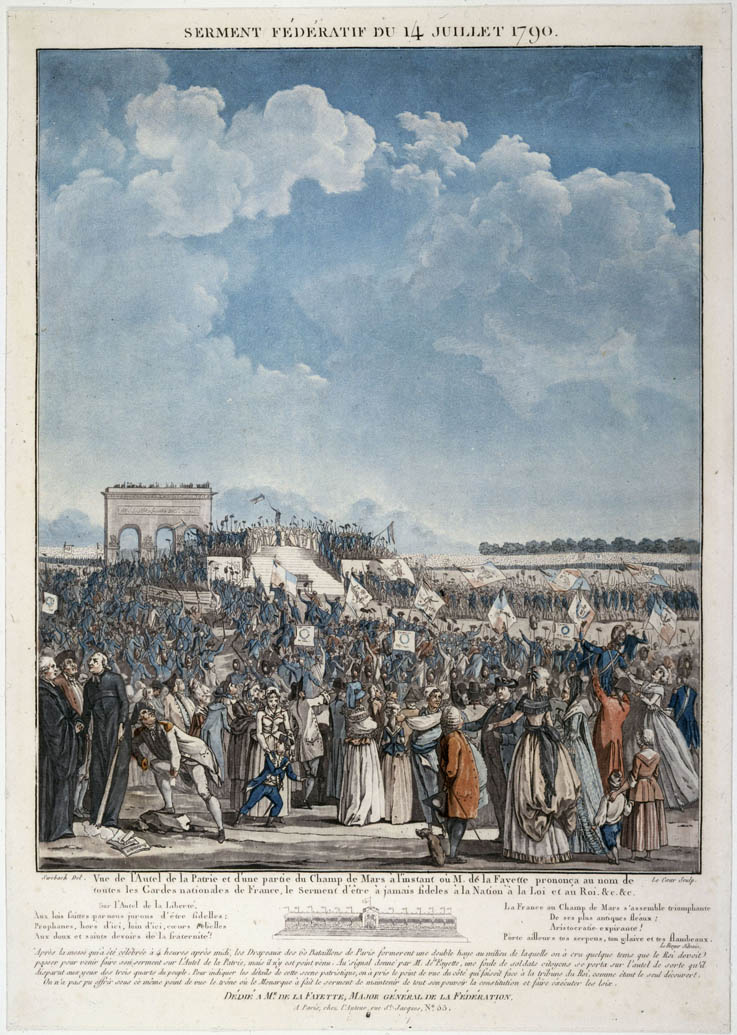

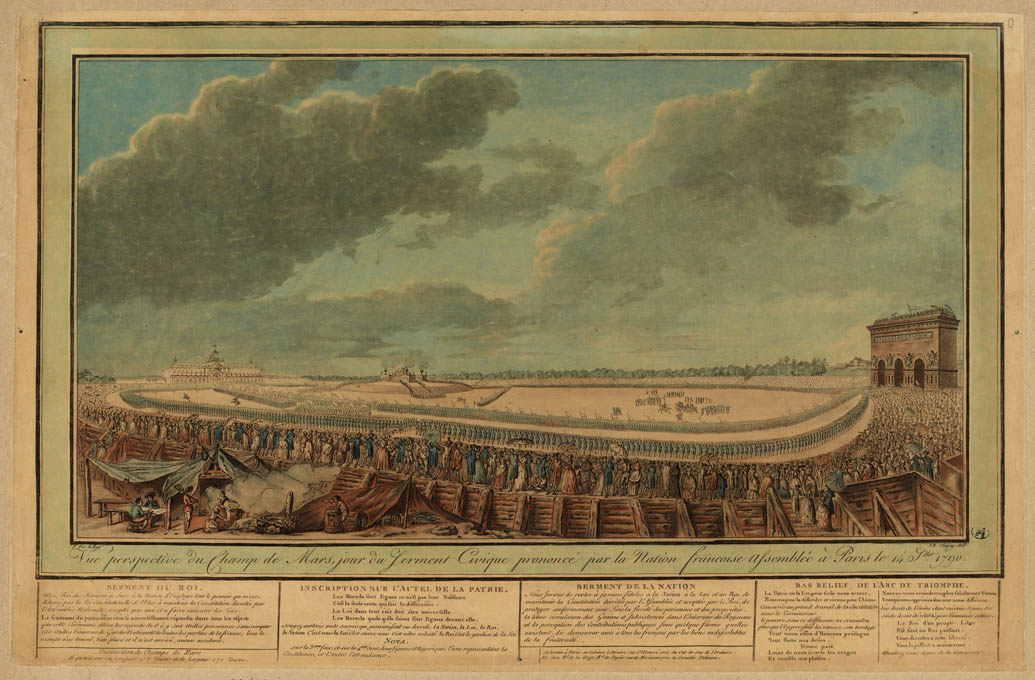

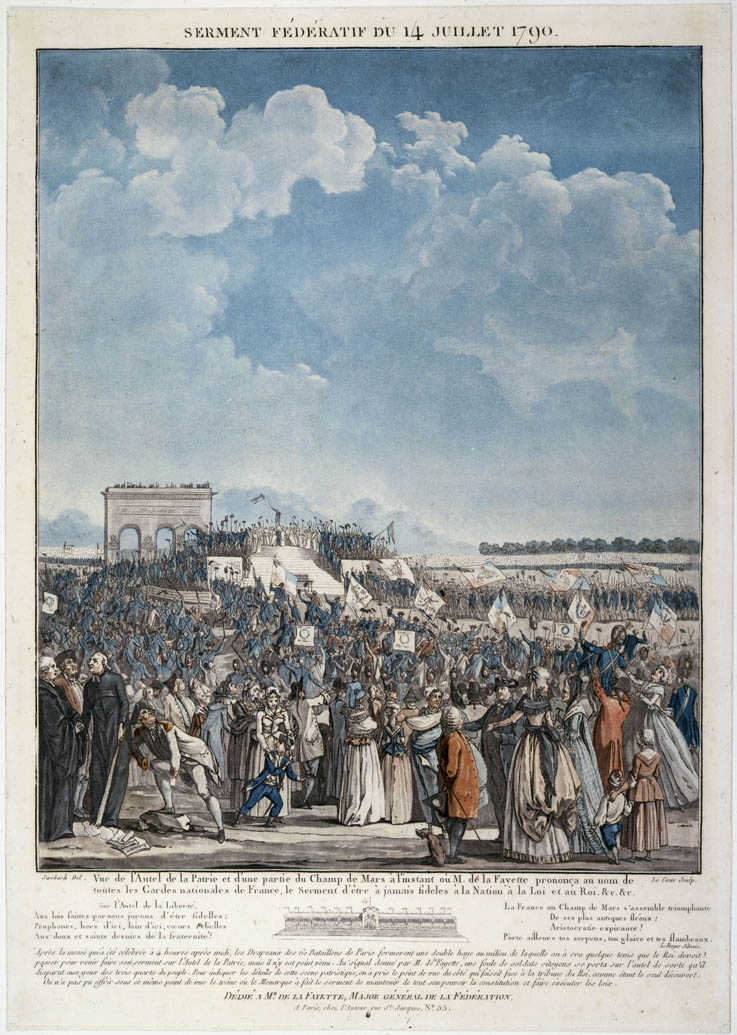

“And the Revolution’s monument is…the void” (Jules Michelet). Today, nothing remains. And yet, on July 14, 1790, from the Seine all the way to the Ecole militaire, under pouring rain, several hundreds of thousands of spectators watched a long parade of 100,000 armed federates, these voluntary soldiers or national guards who had come from all of France’s departments in order to show their support for the Revolution. In the presence of the royal family and deputies, they made an oath “to the Nation, the Law and the King”: exactly one year later after the storming of the Bastille, revolutionaries wanted to celebrate the union of the French people around the constitutional monarchy. In reality, the Revolution was far from over.

Location

Itinerary1 place Joffre

Suggestion

The Champ-de-Mars and its neighborhood

The Festival of the Supreme Being

To find out more…

The Revolution’s greatest monument: the National Grand Arena

Bigger than the Stade de France…To host spectators for the Festival of the Federation, an immense structure in the form of a Roman arena, which could hold approximately 100,000 people, was built. The structure was colossal. The deadlines were so tight that it required the direct participation of Parisians: during the famous “Wheelbarrow days,” Parisians lent a hand in order to erect the enormous knolls of earth whose vestiges were still visible up until the Second Empire (1852-1870).

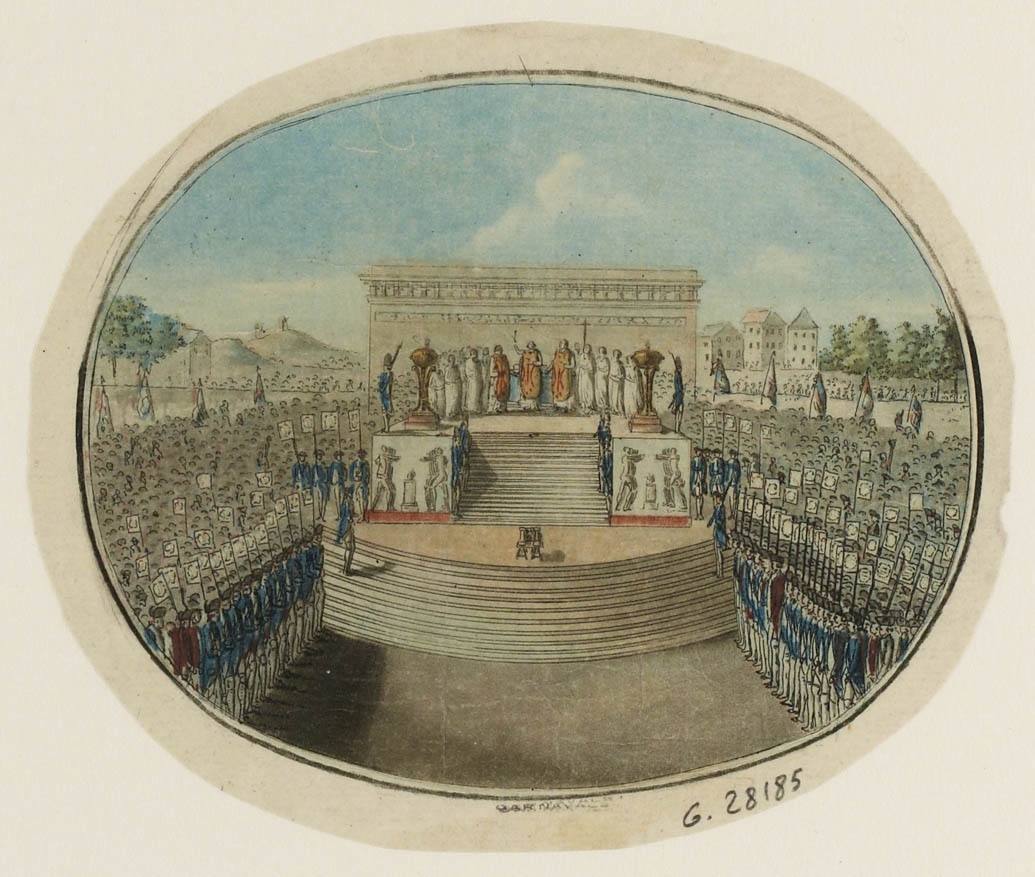

An altar for the Revolution

At the heart of the National Arena, the Nation’s Altar attracted everyone’s attention. Talleyrand, at that time Bishop of Autun, celebrated a large mass here. This is also where La Fayette, commander of the National Guard, deputies, as well as the king, all pledged fealty to the Nation, the Law and the King. The pact that they pronounced together was political, as well as sacred. Often made out of wood, most of the Nation’s altars no longer exist today. However, at the time they were a very common sight since, starting in 1792, they had become mandatory in each municipality.

The Champ-de-Mars: united together?

On July 14, 1790, participants in the Parisian Festival of the Federation pledged an oath to the Nation, the Law, and the King. At that time, when one pledged an oath, it was a real oath. However, we should not be deceived by the images of unity, which were immediately created. United together? Not really. No one asked women, slaves or the poor how they felt. Behind the façade of unity, the French were very much divided. And then the king himself, who never left his seat in the stands, did not keep his promise: he would betray his people a year later when trying to flee the country.