Rue Meslay and Revolutionaries from around the World

Before the Revolution, and partly out of strategy, Louis XVI welcomed revolutionaries to his kingdom who were forced to leave their own country. Paris thus hosted the diaspora of Dutch, Genevan, Polish, Italian and Belgian patriots. When the Revolution broke out in 1789, they did not remain inactive, but participated, for example, in the storming of the Bastille, and an important deputy like Mirabeau could even count on the help of several Dutch assistants! Afterwards, the Revolution in Paris seemed to present a universal revolutionary utopia. Consequently, the French capital attracted those who hoped to bring freedom to the entire world.

To find out more…

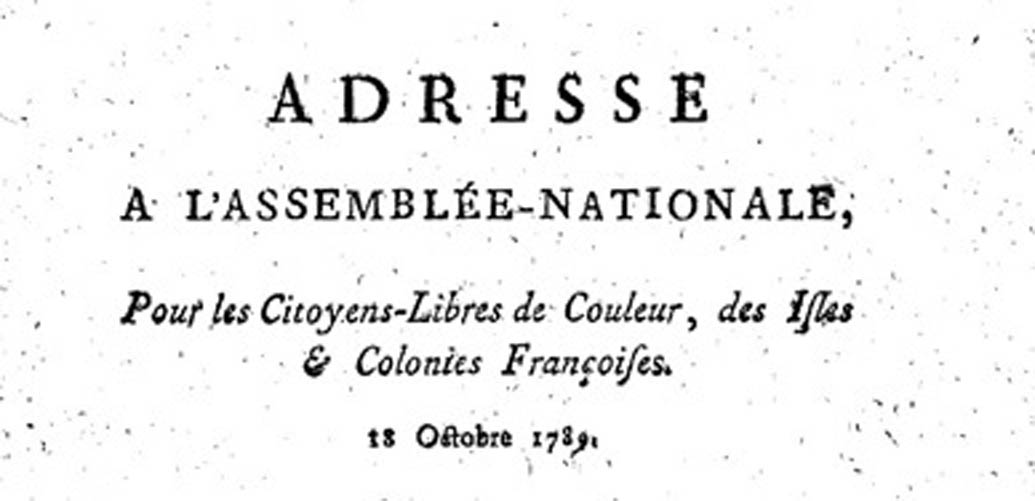

Julien Raimond, leader of the free people of color

Julien Raimond lived here, but you’ve probably never heard of him before. And yet, during the Revolution, he was one of the leaders of those who were called “free people of color”: living in the colonies or sometimes in Mainland France, these men and women were not considered white or slaves. They were free, but underwent great discrimination due the color of their skin. Owner of an indigo plantation in Saint-Domingue, Julien Raimond campaigned throughout the 1780s for the end of color-based prejudice and for equality with whites. He saw the Revolution as an opportunity: in 1789, he joined the Society of American Colonists with Vincent Ogé. Thanks to his principled work, equal rights for free people of color were recognized in 1792, two years before the end of slavery.

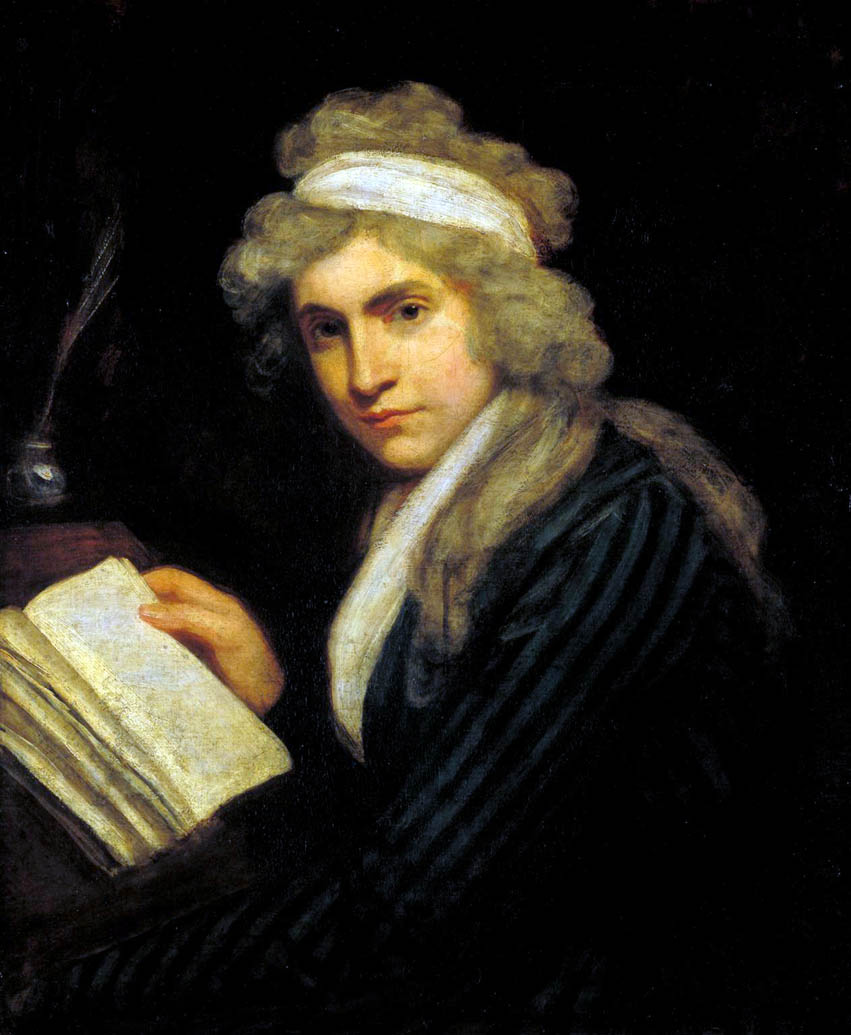

Mary Wollstonecraft, for women’s rights

When we think of defending women’s rights during the Revolution, we think of Olympe de Gouges and the Declaration of the Rights of Women and the Female Citizen (1791). And yet, the Englishwoman, Mary Wollstonecraft, who lived on the rue Meslée for two years (currently rue Meslay) during the Revolution, played a much larger role in the equality of the sexes. Fascinated by the French Revolution and far too radically-minded for England, she moved to Paris between 1792 and 1794, where she got involved with exiled British patriots, as well as with the Girondins, who were moderate Republicans. Above all, she was the author of the essay Defense of the Rights of Women (1792), a manifesto on women’s rights, and especially the right to an education.